A Puppy for Christmas - What a Great Idea?

A puppy is for life and not just for Christmas and I could not agree more! Yet, getting a puppy at Christmas time is a great opportunity for both socialisation and settling your puppy in.

WHAT ARE THE PROS & CONS OF GETTING A PUPPY AT CHRISTMAS?

I am also not talking about giving someone a puppy for Christmas as a surprise or buying a puppy on impulse. I am talking about a long awaited puppy who - for no other reason than the mother coming into season at a certain time of year - comes home for Christmas.

Or a family may have decided to adopt a new rescue dog home at this time of the year because they have more time to settle him in. Christmas is the time when everyone is very social and off work so by definition it should be a great time to get a puppy or a rescue dog.

There are also risks during this busy time; one is that we are flooding the puppy by just putting him/her into a situation with a lot of new stimuli but without creating a positive association. An example would be a very busy Christmas lunch with a lot of loud people around scaring the puppy. Another challenge is that some puppy pre-school classes do not run during the Christmas period. So you will need to make sure you get organised beforehand.

If you get a rescue dog, try to give them a few days (depending on the dog) to settle in at home and get used to the new environment and family members. While we are well and truly past the critical socialisation period, there's still a lot you can do to make them feel comfortable.

Do not rush to the dog park! This dog needs to settle in with you and if he is not well socialised with other dogs, rushing to the off leash area is definitely not a good idea.

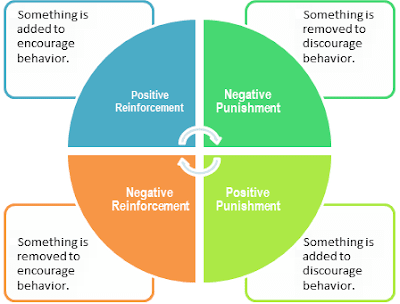

Socialisation at a basic level is respondent conditioning – creating an association between two stimuli and in the case of puppy socialisation, hopefully a positive one! For me, socialisation is the process of learning how to navigate and behave in a world that is not made for dogs! It means developing coping mechanism that will work in 2017 and beyond.

Socialisation was less of a topic for trainers and owners 20 to 30 years ago, not because puppies did not need it, but because for the most part dogs did it themselves. It was still common for them to wander the neighbourhood, hang out with other dogs, go through the garbage bins, get into the odd altercation with other dogs or get hit by a car. It was no big deal and not a big problem.

I do not glorify these times, all I am saying is that things have changed and socialisation is paramount for puppies.

We have to socialise them to different kind of humans, moving objects, other puppies, dogs, animals, surfaces, sounds, environments etc. in a positive way.

If you are looking for a check list, this is a great resource from the Pet Professional Guild.

This process has to happen at the puppy’s pace and the puppy needs to be able to make choices. If the puppy backs off and needs more space and time then it is the puppy’s choice. It also has to have a positive outcome. Exposure alone is not enough, neither is habituation!

There is always a certain risk of disease and it needs to be weighed against the risk of inadequate socialisation. Depending on the geographic area, there will be more or less opportunities. In any case the dog park has to be avoided completely. Other areas where there were a lot of dogs should be a no go for puppies too, not only because of the risk of disease but the risk of inappropriate social interaction.

But there are a lot of things that can be done...

HOW DO YOU ENSURE PROPER SOCIALISATION TAKES PLACE?

1) Organise a couple of puppy parties: one with neighbours to come and play with the new puppy, one for friends and one for the extended family. Do not scare the puppy and it is better to have a few people over more often than one big party.

2) Take the puppy to the coffee shop to experience what a lot of people do these days with their dogs, at least in our coffee society in Sydney. If necessary, keep the puppy on your lap.

3) Sit in front of the local emergency department, where the puppy sees crutches, wheel chairs, hears helicopters and ambulances all whilst feeding her breakfast. Pair each experience with something positive (food, toys, play….).

4) Start leaving the puppy alone for very short period of times and start crate training during the night.

5) Take the puppy for short walks in safe places with different surfaces. Cover easy things like grass, roads, dirt and sand first and only gradually introducing stairs, grades, or bridges. A lot can be done in your or your friends’ backyard.

6) Get them used to the sounds of the household (if not already done by the breeder), power and garden tools, cars, trucks, planes. There are both CDs and apps out there that can assist you with this process.

7) Enrol in one or more good puppy classes. Most trainers will enrol in more than on puppy class because they know there is only a very short time for socialisation.

A word on making the puppy sleep in the laundry or any other isolated place: I do not recommend doing this. The puppy has just left her mother, her siblings and everything else they knew. They need to learn to be on their own and will not cope with isolation. Isolating a puppy at that age can create separation anxiety issues later.

Crate train the pup and keep them with you for the first few weeks. In time your puppy will learn to be on their own.

And no, you cannot socialise your puppies later. Once they are past the critical socialisation period (after 12-16 weeks depending on the pup) you have missed it for good!

I also do not think you can ‘over socialise’ a puppy if done properly. But if you do not work at the individual puppy’s pace and confidence levels you might scare her. To scare a puppy during the critical socialisation period can have life long effects and potentially create a fearful dog. But this is called flooding not socialisation.

Do not buy a puppy on impulse and if you do not want the dog don’t get the puppy!

Barbara Hodel has been involved in dog training for the last 16 years. She has completed a Certificate IV in Companion Animal Services and a Diploma in CBST (Canine Behaviour Science and Technology) and a Delta-accredited instructor since 2007. She's also the President of the Pet Professional Guild Australia (PPGA).

WHAT ARE THE PROS & CONS OF GETTING A PUPPY AT CHRISTMAS?

I am also not talking about giving someone a puppy for Christmas as a surprise or buying a puppy on impulse. I am talking about a long awaited puppy who - for no other reason than the mother coming into season at a certain time of year - comes home for Christmas.

Or a family may have decided to adopt a new rescue dog home at this time of the year because they have more time to settle him in. Christmas is the time when everyone is very social and off work so by definition it should be a great time to get a puppy or a rescue dog.

There are also risks during this busy time; one is that we are flooding the puppy by just putting him/her into a situation with a lot of new stimuli but without creating a positive association. An example would be a very busy Christmas lunch with a lot of loud people around scaring the puppy. Another challenge is that some puppy pre-school classes do not run during the Christmas period. So you will need to make sure you get organised beforehand.

If you get a rescue dog, try to give them a few days (depending on the dog) to settle in at home and get used to the new environment and family members. While we are well and truly past the critical socialisation period, there's still a lot you can do to make them feel comfortable.

Do not rush to the dog park! This dog needs to settle in with you and if he is not well socialised with other dogs, rushing to the off leash area is definitely not a good idea.

Get him used to the routine in the new household first, creating a lot of positive association.

Once he feels comfortable at home, take him out for short walks, keeping a close eye on what might scare him. Take a lot of treats with you so you can associate scary stimuli with something positive.

If your dog stops taking treats this is a clear indication that he/she is over threshold and you might want to back off.

Once he feels comfortable at home, take him out for short walks, keeping a close eye on what might scare him. Take a lot of treats with you so you can associate scary stimuli with something positive.

If your dog stops taking treats this is a clear indication that he/she is over threshold and you might want to back off.

Socialisation at a basic level is respondent conditioning – creating an association between two stimuli and in the case of puppy socialisation, hopefully a positive one! For me, socialisation is the process of learning how to navigate and behave in a world that is not made for dogs! It means developing coping mechanism that will work in 2017 and beyond.

Socialisation was less of a topic for trainers and owners 20 to 30 years ago, not because puppies did not need it, but because for the most part dogs did it themselves. It was still common for them to wander the neighbourhood, hang out with other dogs, go through the garbage bins, get into the odd altercation with other dogs or get hit by a car. It was no big deal and not a big problem.

|

| Puppy Chillax (14 weeks) explores dam with Zorba (14 years) |

We have to socialise them to different kind of humans, moving objects, other puppies, dogs, animals, surfaces, sounds, environments etc. in a positive way.

If you are looking for a check list, this is a great resource from the Pet Professional Guild.

This process has to happen at the puppy’s pace and the puppy needs to be able to make choices. If the puppy backs off and needs more space and time then it is the puppy’s choice. It also has to have a positive outcome. Exposure alone is not enough, neither is habituation!

The assumption that puppies learn to interact appropriately with other dogs by being in the litter with their siblings is plain wrong. Puppies will learn bite inhibition, stalking, playing, rumbling etc but they all look the same and are the same size. This process is habituation and is part of socialisation.

But they also need to learn to interact with puppies of different looks and temperaments. That only happens when playing with unknown puppies before the critical socialisation period closes.

There are some essential life skills your puppy needs to learn when it comes in contact with

other dogs and puppies like being calm in the presence of other puppies.

This means learning how to play appropriately in carefully managed off leash play sessions and short meet and greets.

We should never underestimate the importance of play. All animals including humans learn a lot of their interpersonal skills during play. I am concerned with the new trend in Australian puppy pre-schools that has eliminated play completely. While most owners are able to cover most socialisation aspects, hardly anyone has access to puppies of a similar age.

A puppy pre-school without carefully supervised off leash interaction is a lost opportunity. A good puppy class also provides information on the usual - but for novice puppy owners often unexpected challenges - like house training, bite inhibition, sleeping at night, appropriate interaction with children and proper socialisation.

There are some essential life skills your puppy needs to learn when it comes in contact with

other dogs and puppies like being calm in the presence of other puppies.

This means learning how to play appropriately in carefully managed off leash play sessions and short meet and greets.

We should never underestimate the importance of play. All animals including humans learn a lot of their interpersonal skills during play. I am concerned with the new trend in Australian puppy pre-schools that has eliminated play completely. While most owners are able to cover most socialisation aspects, hardly anyone has access to puppies of a similar age.

A puppy pre-school without carefully supervised off leash interaction is a lost opportunity. A good puppy class also provides information on the usual - but for novice puppy owners often unexpected challenges - like house training, bite inhibition, sleeping at night, appropriate interaction with children and proper socialisation.

It shows the owner how to teach the puppies using management and positive reinforcement methods. It also teaches the owners how to train their puppy some basics such as name recognition, pay attention, sit, lie down, come when called and a few tricks.

There is always a certain risk of disease and it needs to be weighed against the risk of inadequate socialisation. Depending on the geographic area, there will be more or less opportunities. In any case the dog park has to be avoided completely. Other areas where there were a lot of dogs should be a no go for puppies too, not only because of the risk of disease but the risk of inappropriate social interaction.

But there are a lot of things that can be done...

HOW DO YOU ENSURE PROPER SOCIALISATION TAKES PLACE?

1) Organise a couple of puppy parties: one with neighbours to come and play with the new puppy, one for friends and one for the extended family. Do not scare the puppy and it is better to have a few people over more often than one big party.

2) Take the puppy to the coffee shop to experience what a lot of people do these days with their dogs, at least in our coffee society in Sydney. If necessary, keep the puppy on your lap.

3) Sit in front of the local emergency department, where the puppy sees crutches, wheel chairs, hears helicopters and ambulances all whilst feeding her breakfast. Pair each experience with something positive (food, toys, play….).

4) Start leaving the puppy alone for very short period of times and start crate training during the night.

5) Take the puppy for short walks in safe places with different surfaces. Cover easy things like grass, roads, dirt and sand first and only gradually introducing stairs, grades, or bridges. A lot can be done in your or your friends’ backyard.

6) Get them used to the sounds of the household (if not already done by the breeder), power and garden tools, cars, trucks, planes. There are both CDs and apps out there that can assist you with this process.

7) Enrol in one or more good puppy classes. Most trainers will enrol in more than on puppy class because they know there is only a very short time for socialisation.

A word on making the puppy sleep in the laundry or any other isolated place: I do not recommend doing this. The puppy has just left her mother, her siblings and everything else they knew. They need to learn to be on their own and will not cope with isolation. Isolating a puppy at that age can create separation anxiety issues later.

Crate train the pup and keep them with you for the first few weeks. In time your puppy will learn to be on their own.

And no, you cannot socialise your puppies later. Once they are past the critical socialisation period (after 12-16 weeks depending on the pup) you have missed it for good!

I also do not think you can ‘over socialise’ a puppy if done properly. But if you do not work at the individual puppy’s pace and confidence levels you might scare her. To scare a puppy during the critical socialisation period can have life long effects and potentially create a fearful dog. But this is called flooding not socialisation.

Do not buy a puppy on impulse and if you do not want the dog don’t get the puppy!

Barbara Hodel has been involved in dog training for the last 16 years. She has completed a Certificate IV in Companion Animal Services and a Diploma in CBST (Canine Behaviour Science and Technology) and a Delta-accredited instructor since 2007. She's also the President of the Pet Professional Guild Australia (PPGA).

She has been running Goodog Positive Dog Training on the Northern Beaches Sydney for the last nine years, running classes on all levels as well as workshops and agility fun classes.

www.goodog.com.au

www.goodog.com.au